Son of Classical Economics

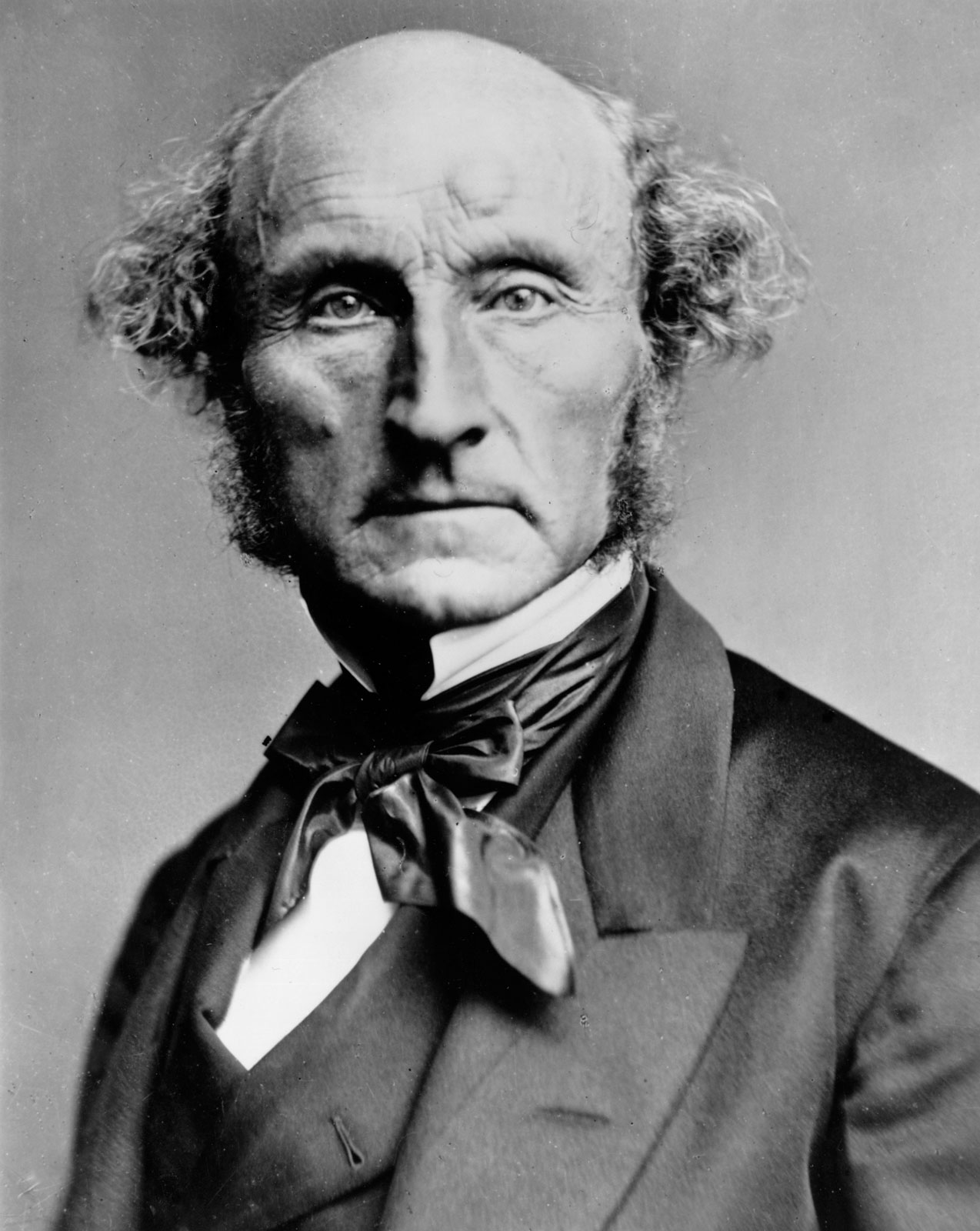

John Stuart Mill was born on May 20, 1806, in London, England, as the son of James Mill, a prominent economist and philosopher. Raised under an intense and highly structured education designed by his father, he was reading Greek by the age of three and studying advanced economics, logic, and philosophy by his teenage years. Influenced by Jeremy Bentham’s utilitarianism, he became a leading intellectual force in 19th-century Britain, contributing significantly to political economy, philosophy, and social reform. Unlike his father and earlier classical economists, Mill’s work took a more nuanced approach to free markets, individual liberty, and government intervention, making him a pivotal figure in the transition from classical to modern economic thought.

Mill’s most significant economic work, Principles of Political Economy (1848), became one of the most widely used economic texts of the 19th century. While he upheld classical economic principles, such as free markets, division of labor, and Ricardian rent theory, he also recognized market failures and social inequalities that required corrective policies. He argued that while laissez-faire was the best general approach, government intervention was sometimes necessary to address poverty, education, and monopolies. He introduced the idea that the laws of production are fixed by nature, but the distribution of wealth is a matter of human policy, opening the door for later redistributive economic theories.

A major contribution of Mill was his refinement of utilitarianism. In his work Utilitarianism (1863), he expanded upon Bentham’s ideas by emphasizing qualitative differences in pleasures, arguing that intellectual and moral fulfillment held greater value than mere physical gratification. This distinction influenced later debates on welfare economics and social justice.

Mill also addressed population concerns, adopting a Malthusian perspective but believing that education and social progress could lead to voluntary population control, mitigating the crises predicted by Thomas Malthus. He supported women’s rights and labor reforms, arguing in The Subjection of Women (1869) that gender equality was essential for a just society. His views on democracy were similarly progressive, advocating for universal suffrage but with an educated electorate, reflecting a balance between his father’s elitist tendencies and his own belief in participatory democracy.

Despite being a staunch supporter of free trade, Mill acknowledged the potential harms of industrial capitalism, such as worker exploitation and excessive inequality. He supported cooperative enterprises and labor unions as a way to empower workers without abandoning market principles. His ideas on the stationary state economy, where growth slows but well-being continues to improve through social and technological progress, anticipated later discussions on sustainability and post-growth economics.

John Stuart Mill died on May 8, 1873, but his influence remained profound. His work bridged the gap between classical liberalism and modern social democracy, inspiring later thinkers such as John Maynard Keynes and Amartya Sen. By integrating classical economics with ethical and social concerns, he helped shape modern economic policies that balance market efficiency with social justice.